Could Vitamin B12 deficiency and preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome be related?

Question: Is there an association between low Vitamin B12 levels and preeclampsia?

Answer:

There is an association between low levels of B12 in the bloodstream during pregnancy and an increased risk for preeclampsia, though research suggests that it is likely due to shared metabolic pathways rather than a direct relationship.

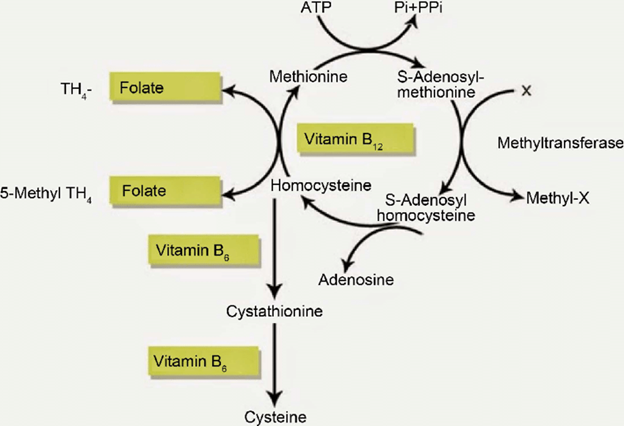

A ‘metabolic pathway’ is a complex series of chemical reactions that happen inside a cell. Enzymes within the body create reactions that convert one substance into a final product that can be used by the body's cells. The metabolic cycle in which B vitamins, including B12, interact with enzymes in the body is quite complicated. A low B12 level has been linked with poor pregnancy outcomes such as low birthweight infants and preterm birth (Rogne 2017), so we recommend reaching out to your healthcare provider to discuss further if it is a concern for you.

The B12 and Homocysteine Metabolic Pathway

Illustration 1. We share this image to illustrate the complexity of the metabolic pathway that vitamin B12 is involved in.

What the research tells us

A recent meta-analysis of research (which included 19 individual studies for a total of 3211 cases) found that women with preeclampsia had significantly lower serum vitamin B12 levels compared with pregnant women without preeclampsia (Mardali 2020). A normal serum level of vitamin B12 in your bloodstream is generally between 200 and 900 picograms per milliliter (pg/mL). This meta-analysis showed that average vitamin B12 levels were on average 15.24 pg/mL lower among women with preeclampsia when compared to those without. While this was not a big difference in blood levels of B12, it was statistically significant, which makes it interesting to researchers.

However, the individual studies compiled into the meta-analysis reported widely differing outcomes, which may reflect the specific populations they were studying. The smaller studies that make up a meta-analysis can sometimes show larger effects than in a single study that has a lot more participants. The authors of the meta-analysis examined if maternal serum homocysteine levels, folic acid supplementation, or gestational age could explain the variation in the results, but none significantly explained the difference between studies. That makes this finding hard to interpret beyond the knowledge that women with preeclampsia have lower B12 levels because it is not clear why different studies got different results. That suggests that there might be some other factors in addition to the measurable vitamin deficiency in the development of preeclampsia.

What is vitamin B12 and why does it matter?

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin found mainly in meat, eggs, and dairy products. B12 is one of eight B vitamins involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body. It is one molecule needed to copy our DNA when cells divide. In both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, B12 helps to create red blood cells and provide the body energy. A deficiency in B12 can result in a type of anemia called megaloblastic anemia that makes people tired and weak.

Vitamin B12 and its related B-complex vitamins B9 (also known as folate) and B2 (also known as riboflavin) are involved in biochemical reactions in the body with amino acids, homocysteine, cysteine and methionine and other metabolites that the body needs to function (Serrano 2018; Mardali 2020). If the body does not have enough of these B vitamins, not enough homocysteine is converted, leading to higher levels of homocysteine concentrations in the bloodstream.

Higher levels of homocysteine have been associated with increased oxidative stress and endothelial damage (Serrano 2018), which may increase the risk of developing preeclampsia (Mardali 2020).

So what is the Role of Folic Acid (Vitamin B9) during pregnancy?

Vitamin B9 (folate or folic acid) plays a key role in fertility, pregnancy and the health of the baby. Folate is found naturally in foods such as leafy green vegetables, eggs, and citrus fruits, while folic acid is the synthetic version used in fortified foods and supplements. Folic acid has been well-studied for its ability to prevent neural tube defects, which is why women who are pregnant or trying to conceive are encouraged to take a prenatal vitamin that includes folic acid.

However, genetics can affect how well your body converts vitamin B9 (folic acid) to its active form, methylfolate. Anywhere between 25-60% of the US population have a variation in one of their MTHFR genes that changes how they convert folic acid. (Read our “Ask An Expert” article on the MTHFR gene for further information.)

Methylfolate, the active form of folic acid, plays a role in converting homocysteine into methionine, an essential amino acid in humans. So if methylfolate is lacking (perhaps due to the common MTHFR genetic mutation), homocysteine is not converted and may build up to harmful levels. (see illustration 1.)

Therefore, some clinicians and researchers have asked: could we just give more folic acid to women to decrease homocysteine in the bloodstream and thereby decrease the risk of preeclampsia? The research unfortunately does not support this. One recent clinical trial randomized 2301 women in five countries to high dose supplementation (4.0mg folic acid a day) from around 14 weeks gestation to delivery, but did not find a significant effect on rates of developing preeclampsia (Wen 2018).

Homocysteine and preeclampsia

Higher levels of homocysteine have been associated with hypertension, heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and preeclampsia, among several other conditions. In bloodwork tests of women with preeclampsia, they had higher rates of homocysteine – but whether that is because of lower levels of vitamins B12 and B9, or coincidental because of some other metabolic process happening during a preeclamptic pregnancy, is still not clear.

Recent research on the relationship between homocysteine, B12, and the risk for preeclampsia has shown mixed results. A few smaller studies within the last five years (2016 or later) have found measurable association between vitamin B12 concentrations in the mothers’ blood and preeclampsia. Two larger studies with over 1000 participants found no significant association. Table 1 below gives a further list of these studies and their findings.

| Reference | Study Design | Country | Participants | Vitamin B12 levels of women with PE compared to those without PE | Folate (B9) levels of women with PE compared to those without PE | Homocysteine levels of women with PE compared to those without PE |

|

Shahbazian et al 2016 |

Case-control |

Iran |

101 (51 with PE, 50 controls) |

Lower |

Lower |

Higher |

|

Serrano et al 2018 |

Case-control |

Colombia |

7074 (2978 with PE, 4096 controls) |

No significant difference |

Lower |

Higher |

|

Osunkalu et al 2018 |

Case-control |

Nigeria |

400 (200 with PE, 200 controls) |

No significant difference |

No significant difference |

Higher |

|

Zhao and Zeng 2019 |

Case-control |

China |

226 (82 with PE, 66 with GH, 78 controls) |

Lower |

Lower |

Higher |

|

Pisal et al 2019 |

Case-control |

India |

800 (350 with PE, 450 controls) |

Higher |

Higher |

Higher |

|

Liu et al 2020 |

Case-control |

China |

1163 (563 with adverse pregnancy outcome, 600 controls) |

No significant difference |

Lower |

Higher |

What does this mean for me?

As with all pregnancies, a healthy diet that includes plenty of the vitamin B complex is important. You will likely be encouraged by your health care provider to also take a daily supplement that includes folic acid (usually 400 mg) for your own pregnancy health and the healthy development of your baby. Research has not yet progressed far enough to inform routine clinical care practice beyond these standard recommendations. If you know you have a B12 deficiency or difficulty processing folic acid, you should discuss any special considerations with your doctor, or seek out a specialist who understands these metabolic factors on preeclampsia.

As always, more research is almost always needed to verify and clarify research findings.

About the Authors

Maggie Woo Kinshella is a Research Coordinator and PhD Candidate in Reproductive and Developmental Sciences at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of British Colombia. Born and raised in Vancouver, Maggie obtained a MA in Cultural Medical Anthropology and a BA in Psychology and Anthropology from the University of British Colombia. Her doctoral research examines maternal diet and pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, where 99% of global maternal deaths due to preeclampsia and other complications occur.

Maggie Woo Kinshella is a Research Coordinator and PhD Candidate in Reproductive and Developmental Sciences at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of British Colombia. Born and raised in Vancouver, Maggie obtained a MA in Cultural Medical Anthropology and a BA in Psychology and Anthropology from the University of British Colombia. Her doctoral research examines maternal diet and pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, where 99% of global maternal deaths due to preeclampsia and other complications occur.

Caryn Rogers is the Senior Science Writer at the Preeclampsia Foundation. As a community moderator, she has dedicated 15 years to creating clear, understandable explanations of the science underpinning preeclampsia so that women can use this knowledge to protect their own interests. Published in the Journal of Medicine and Philosophy and in Pregnancy Hypertension, Caryn uses her experience with philosophy of evolutionary medicine to support the Preeclampsia Foundation's mission. She developed preeclampsia with severe features at 33 weeks in 2002. After a week in the NICU, her son recovered well. Her daughter was born at 39 weeks after a normotensive pregnancy.

Caryn Rogers is the Senior Science Writer at the Preeclampsia Foundation. As a community moderator, she has dedicated 15 years to creating clear, understandable explanations of the science underpinning preeclampsia so that women can use this knowledge to protect their own interests. Published in the Journal of Medicine and Philosophy and in Pregnancy Hypertension, Caryn uses her experience with philosophy of evolutionary medicine to support the Preeclampsia Foundation's mission. She developed preeclampsia with severe features at 33 weeks in 2002. After a week in the NICU, her son recovered well. Her daughter was born at 39 weeks after a normotensive pregnancy.

ABOUT "ASK AN EXPERT"

This article is a response to research questions submitted by Preeclampsia Registry participants. If you have a research idea or question, enroll in the registry or login and select "Submit a Research Question" from your registry home page.

Related Articles

Is there a connection between maternal diet and preeclampsia? The PRECISE Network research team and I recently completed an evidence review to compile information on maternal nutritional factors that...

Question: Progesterone supplementation - first trimester and beyond - can it help the vascular constriction by keeping the smooth muscle relaxed (17HP shots), and is it associated with early supplemen...

Ask An Expert Question: Low dose aspirin is prescribed in pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia. Some women, however, experience aspirin resistance, where aspirin treatment is ineffective. Why doesn&rsquo...

Question: I would like to know the correlation and prevalence of HELLP / Preeclampsia and Polycystic Kidney Disease. Answer: Women with polycystic kidney disease (PKD) are at higher risk of a...

Several genes in our bodies have been linked -- to varying degrees -- to our chance of developing preeclampsia. A gene is a region of your DNA that holds the instruction manual for making...